In the age of “childhood obesity” rhetoric amid the global panic around adiposity, one anonymous writer writes of her experiences as a fat child and adolescent in medical care. Sadly, the physician’s attempts to “control her weight” led not only to disconnection from her body, but also to a dangerous eating disorder. As much of our readership is aware, there is currently a “starvation trial” involving intermittent fasting for adolescents being conducted in Australia. Many Health At Every Size (HAES®) advocates and several professional organizations have spoken out about the potential harms of this trial, giving rise to more global awareness of the negative impacts of restrictive diets on children. Given this context, this is a particularly poignant piece about the very real harms of weight management practices with children and teens.

Dear Dr. “X,”

I hope this letter makes its way to you. It has been many years since I’ve visited your practice and I’m not sure if I have the right address or if a well-meaning assistant might deem this letter ill-suited for your undoubtedly busy schedule. I’ll admit it’s long, and possibly difficult to get through, but I promise it’s worth the read.

I was a patient of yours for most of my later childhood and adolescence. And to my recollection, it seems I came to see you quite a bit: my parents were fairly responsive to even the faintest signs of a cold. I suspect you hardly remember me, and that’s fine given the number of patients you see, but nevertheless you came to play quite a pivotal role in my life.

You see I was a rather large kid, from a pretty early age. I remember being told, probably before the age of 10, that I was somewhere in the 90th percentile of weight. And despite coming to your office many, many times over the years for a variety of reasons, mostly upper-respiratory infections, I always managed to leave with a prescription for weight loss.

Now before I get any further, I want to stress that I fully believe that you were doing what you thought was best and what the medical literature of the time, and even today in many places, would suggest. Nevertheless, the messages I received from you would be some of the most damaging messages I’ve received in my life.

I was young and marinating in a slew of messages from all around – TV stars, magazine covers, the popular kids at school, mannequins at department stores – all telling me that thinness, (and as this was the 90’s and 00’s – extreme thinness) was the ideal. Was cool, was hot, was normal. But, I also had a fair amount of messaging that combated these messages. I knew the models were airbrushed, I knew celebrities were abnormalities. I knew I didn’t look like them, but I didn’t expect to either. But then I heard the science. The news reports. The fears about the obesity epidemic, the idea that one could be too fat and that it wasn’t just an issue of aesthetics, but an issue of health. I could die because I was too fat. I was awash in a sea of confusion.

And then I heard it from you: at the age of probably 10 or 11, on the verge of puberty, my body putting on weight in preparation for a growth spurt. I was too big. My BMI was not in the acceptable range. I saw the charts. I was interrogated about my diet, my exercise. My mom and I. And believe it or not, at the time I was a relatively active kid: I loved swimming and bike riding, and I took dance lessons. My diet wasn’t all that bad either, maybe a little light on the vegetables. But you seemed skeptical. We were told to keep an eye on it, and in later visits, I was told that my weight needed to come down. There was an implied message, whether or not intentional, that I wasn’t taking “it” seriously enough, that I was uncompliant, that I wasn’t trying hard enough.

Again, I grasp that this is/was common medical practice, but can we pause for a moment and consider what happened in this moment? And what happened in the many moments that followed? I was an 11-year-old child – with almost no control over what I could and couldn’t eat, subject to the means of my parents and school. And I get that your intentions were surely more to relate information to my mother – but I was still in the room, learning that I must monitor everything that passed my lips. I was an 11-year-old child – being told that my body was wrong. That it was too big, too much, and that it should be smaller. In context with the world, an exact confirmation of everything it told me every day. In the context, without any further explanation–functionally a verification that the images and messages in the media and external world were right. As a child, I was being told there were good bodies and bad bodies, and that mine was bad. I had looked to the medical community to set me straight on reality, and in that moment, it failed me, and failed me horrifically.

Because an 11-year-old child is incapable of effectively controlling their weight. Because teenagers are incapable of effectively controlling their weight. Because, dammit, adults are nearly incapable of effectively controlling their

weight. How could there be a multi-billion dollar weight loss industry or “obesity-crisis” if they were? The failure rate on attempts to lose weight is between 70-90 percent. And most folks who keep weight off for any period of time are eating less calories in a day than a toddler. These are statistics from peer-reviewed studies that I will include resources to with this letter.

I spent the next 15 years of my life doing everything possible to lose weight and being constantly reminded of my failure. As I’m sure you’re aware, at every doctor’s visit the very first thing that occurs is you get weighed. You cannot imagine the amount of shame I carried at every visit seeing that damn metal slider inch ever farther to the right, despite all my attempts to stop it. I felt dread at every conversation, when it would turn from Bronchitis to BMI.

I know this letter must be difficult to read, and I swear to you my intent is not to cast blame. I know as a physician your calling is to help people. I know that you studied and toiled for years for the privilege of getting to help people. But the standard assumptions of medicine are causing harm and damage, especially to children, and you’re in a prime position to stop it from happening.

Eventually my calorie-counting obsession became an undiagnosed eating disorder. And I was convinced I was healthier than I’d ever been.

Because over the next two years, as an adolescent, I lost 58% of my body weight. With no actual regard to my health – all I cared about was thinness. I was weak, cold all the time, had probably lost most of my muscle mass, was craving food. I grew very close to passing out while doing nothing but standing several times. And of course, I was immensely happy. I had finally done it. I was finally a “proper” BMI, the world accepted me, I had passed my test. I was finally a good person after all these years of struggle. No longer too much. No longer wrong. I waltzed in to your office after a two-year hiatus, with another case of bronchitis, and you barely noticed.

Whereas at every prior visit my weight centered the conversation, this time it was an afterthought. “Oh, I’ve seen you’ve lost some weight.” That was it, perhaps followed by it a “Keep it up.” I was so bewildered. Two years of struggling after a life time of harping on my weight and when I finally did lose weight, there was barely any reaction at all. Today I look back even more incredulously. A teenager loses over half their body weight in two years, and it’s essentially ignored? How does that not raise any red flags? Not even a recommendation for screening for depression, illness, or perhaps an eating disorder? You were talking to a person that at the time was literally starving. Who was dealing with self-harm, who was at serious risk of all manner of serious physical conditions. But it was all rendered invisible because I was a previously fat person who had become the “correct” size. I was a success story.

The thing about this encounter that disheartens me, that fills me with grief, that physically pains me knowing it still must happen every day, is that this isn’t an isolated case. That this isn’t really your fault even, and let me stress again, that for as much a pivotal role you play in my story, that it’s hardly you that bears the brunt of the responsibility. This is a pervasive attitude the runs throughout the medical and science community that seeks to make fat people thin at all costs and, as activists have pointed out, routinely makes the habit of prescribing to fat people what it diagnoses in thin people. My anorexia was invisible because no one would think to look for it in a fat person. My BMI was normal. Even high normal. Therefore, I was healthy. This is despite the fact that people with higher BMI’s are at increased risk for eating disorders compared to thin people.

I struggled with the eating disorder for years – battling the biological urges of my body, gaining weight, losing weight, and then gaining again. I developed intense depression, my self-harm became grave. I felt powerless and at a loss as to why I couldn’t control this one simple thing I had been told all my life that I was supposed to handle. Thankfully, after one terrible night, I scared myself into seeking help. I found a therapist, an eating disorder specialist, and began to heal. I healed, but it took way longer than it might have and caused extra damage along the way. I wasn’t having issues with impulse control, I was quite literally starving. I struggled with bingeing for years until discovering an approach to health that said, “what if your body is how it is, you eat when you’re hungry, stop when you’re full, and let it be.” Miraculously my bingeing behavior virtually stopped overnight.

The approach I ran across is Health at Every Size®. Obviously, I’m a fan of it, and the primary reason I’m writing is to ask you to please investigate it. For the first time in my life, I feel free around food, for the first time in my life, I actually desire both traditionally nutritious foods as well as pleasure foods. My vitals are all great, my weight is stable, I’m seemingly a picture of health. And while my relationship with my body is still very, very strained, I’m finally at a point where I can see a glimmer of a future where that might not be the case. I have difficulty believing any of this would be possible without doctors and health professionals telling me in no uncertain terms that there’s more to health than weight or fat or BMI, and that it in fact, those things matter very little.

Here’s what I see as the important take aways from HAES®:

- We don’t know how to make fat people thin. There are no studies where any but a tiny minority of participants keep weight off for more than 5 years, and those that do are often engaging in just as disordered behaviors as I was.

- Those that regain weight after losing it, often end up at higher weights than they began at. Every attempt pushes that set point higher.

- The intentional pursuit of weight loss harms the body. Those people who have lost and regained a significant amount of weight are at much higher risk for several health conditions. And most people who try to lose weight repeatedly cycle, which is even worse for the body. Weight cycling itself can cause many of the illnesses fatness is usually attributed to.

- Similarly, weight stigma, the shame and guilt and social ostracization faced by fat people (as well as other stigmas such as that of those of poverty or racial minorities) contributes to immense amounts of chronic stress, which has been linked again to the same types of diseases and health issues associated with fatness.

Telling patients their bodies are wrong or too much, etc., and framing obesity as some sort of social contagion contributes to stigma. Perhaps, most importantly, kids are vulnerable. They absorb everything they hear. They are bombarded with messages from everyone and everywhere telling them what they should be. The last thing they need to hear from a trusted authority figure is that there is something wrong with them that don’t have the resources to control. The last thing they need to hear is that they need to change. They need the medical professionals in their life to combat the toxic messages pervasive in the media and culture. They need those professionals to tell them the facts– that everyone’s body is different and that’s okay. Kids need to be encouraged to eat a variety of foods, that taste good and make them feel good, and engage in movement they enjoy – completely apart and absent from talk about weight. I can’t stress enough how valuable such a perspective would have been in my life. For myself and my family to hear it.

I’ve attached to this letter some pages from Health at Every Size, the book by Dr. Linda Bacon. It’s a good starting point that can answer questions and point you to more detailed research. I sincerely hope you’ll investigate what it has to say. And if you somehow still find a weight-neutral perspective is not for you, then I implore you to seriously consider and limit your talk about weight and fat with patients, especially children. I don’t want any child to ever go through what I did, or, god forbid, something even worse. You have the power to actually enact change and be on the front lines, helping people become their most healthy best selves.

All my best wishes for the future,

“Mary”

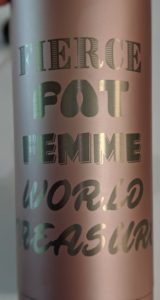

Author Biography: Per the author’s request, both herself and the physician addressed here remain anonymous. Art featured in this blog was produced by the author of this piece. This author is a participant in the WINTER Study (Women’s Illness Narratives Through Eating/Disorder and Remission Study), an ongoing HAES®-informed study of eating disorder experiences led by researcher Erin Harrop, MSW, PhD-C. The WINTER Study has been supported by the Association for Size Diversity and Health through a Health at Every Size® Expansion Grant, and through the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number TL1 TR002318.

via healthateverysizeblog https://ift.tt/2leBkrR

Jenna went to church to sing and celebrate as a worship leader in the contemporary band at her Methodist Church. But then Sister Bonnie-Better-Than-You of the Church of Fatphobia went to work.

Jenna went to church to sing and celebrate as a worship leader in the contemporary band at her Methodist Church. But then Sister Bonnie-Better-Than-You of the Church of Fatphobia went to work.